The RWA is known for its association with pioneering women in the arts, from its founder, Ellen Sharples, to its first female president, Janet Stancomb-Wills. In line with the RWA’s Season of Photography and Women’s History Month, Medi Jones-Williams explores the life and work of Anna Atkins, pioneering photographer and scientist.

A century before the famed Frida Khalo said ‘I paint flowers so they will not die’, the British botanist and illustrator Anna Atkins explored a new photographic technique that promised to preserve plants long after their physical forms had perished. Unsatisfied with the results from the painstaking process of hand-drawing specimens of algae and fern, Atkins pioneered a new approach to accurately record botanical specimens – a photographic printing technique recently developed by a family friend.

This process was called Cyanotype, a name coined by its inventor, the astronomer and Hellenophile Sir John Herschel. The name derives from the Greek words “kyanos” meaning dark blue and “typos” meaning impression. Anna Atkins popularised the use of cyanotype in scientific illustration and is widely believed to have been the first person to use photography to illustrate a book.

Cystoseira granulata. Anna Atkins c.1853. MET Inv. 2005.100.557

Spiraea aruncus (Tyrol). Anna Atkins, c.1853. MET Inv. 2004.172

The first volume of her series on British algae was published in 1843, a year after the cyanotype’s creation. Although women were officially excluded from science and education, botany and scientific illustration were considered appropriate pastimes for well-to-do women like Atkins. Her father, the scientist John George Children, influenced Anna’s foray into these subjects, and she supplied the illustrations for his translation of Lamarck’s Genera of Shells, in 1823.

The cyanotype technique involved coating paper with a light-sensitive solution of iron salts that turns blue when exposed to ultraviolet light. To create a print, an object (in this case, a plant sample), was placed on the coated paper and exposed to the sun for a period of time. The unexposed areas of the paper or fabric remained coated with the iron salts, while the exposed areas developed a blue tint, creating a finely detailed, silhouette of the object. Atkins used this technique to create the first photographic book ever published, Photographs of British algae: Cyanotype Impressions.

Published in several volumes between 1843-1853, the book contains over 400 cyanotype prints of plant specimens, providing detailed visual records of algae that had never before been published. This technique produced an ethereal blue-and-white image of the plants’ delicate and intricate structure. The sharp details, emphasised by the high contrast between the Prussian blue background and the ghostly white skeleton of the plant specimen. These attributes made them particularly popular in the 19th century for both scientific illustration and architectural drawings (hence the term ‘blueprint’).

Atkins continued to work on cyanotype photography, producing images of ferns and other botanical specimens. She also experimented with other photographic techniques, such as the calotype process. However, her cyanotype work remains her most celebrated achievement. Anna Atkins died in 1871, leaving behind a legacy as one of the earliest pioneers of photography and a significant figure in the history of botany.

Cyanotype today

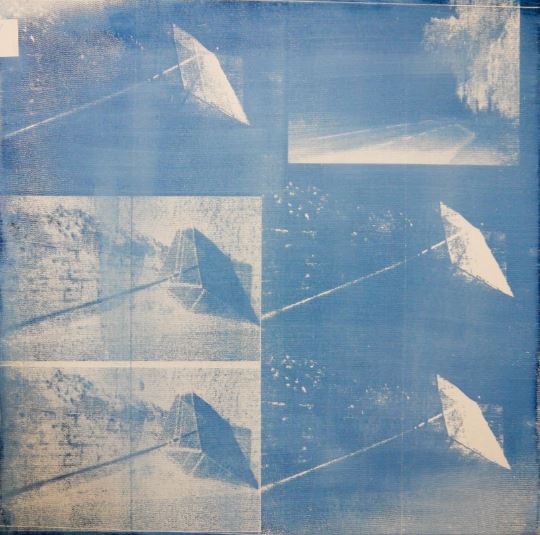

Despite rapid developments in digital photography (everybody can now carry a sophisticated camera in the shape of a smartphone in their back pocket), cyanotype is still used by artists and photographers who appreciate its anachronistic look, bold colours, and scientific significance.

Atkins’ work continues to inspire generations of artists, photographers, and scientists, such as those currently exhibited in the RWA’s Photo Open. For example, the repeated image of an elver net by Niki Hare showcases the versatility of the cyanotype technique. While Martyn Grimmer and Gracie Evans have created haunting images that recall half-forgotten memories from childhood using cyanotype, Rosie Emerson’s Athena uses the technique to transform her model into the Greek goddess, whose helmet and aegis are created through the contrast of underexposed canvas against the Prussian blue portrait.