168 Annual Open - Winterstoke Gallery Tour by Kati Cramp

We are delighted to say that the RWA is reopening from Saturday 17 April - Sunday 9 May 2021. Book tickets for the 168 Annual Open Exhibition HERE

While we have been closed all artworks have been available for purchase online HERE and you can still do this until 9 May

In the RWA’s 168 Annual Open Exhibition, the Winterstoke gallery houses numerous artworks ranging in media and topics. However, some of the pieces that really stood out to me were the portraits. Portraiture is one of the oldest traditions in art and it is always fascinating to seeing how modern artists take on this legacy in unique and innovative ways. Before the invention of photography, portraiture was the only means by which a person’s appearance could be recorded, and often artists strived to capture not just the physical aspects of their sitter, but also some form of their essence. This idea of understanding between artist and subject feels somehow more precious in current times; with relationships and human connection straining under the weight of lockdown measures, how we view and experience the people around us has never felt more crucial.

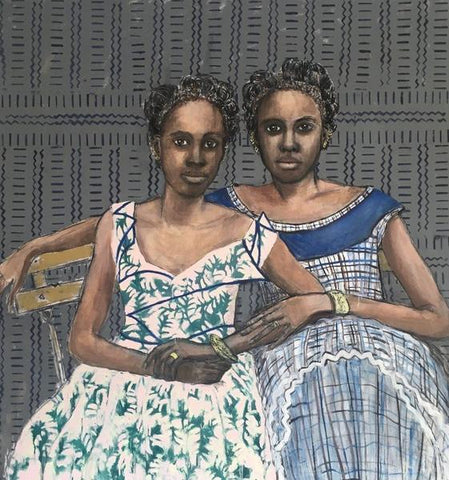

Renee Spierdijk’s ‘Sisters (After Seydou Keita)’ encapsulates these ideas. Created in response to an untitled photograph by the Milanese photographer Seydou Keita, Spierdijk has depicted the two figures as sisters. Although this was speculation on the part of the artist, it is easy to see why she has come to this conclusion. The girls not only have similar facial attributes marking them as relations, but the comfortable way that they are sitting, leaning on one another, heads tilted slightly together, gives the viewer the sense of a close relationship. Spierdijk has emphasised this through her composition and use of strong lines; the line of the girl’s arms and shoulders makes them appear almost as one form: a single familial unit. The piece feels like an important addition to the exhibition, I think this strong sense of relationship, in a time when so many of us are separated from even our close families not only reminds us of a familiar past but is also a comforting image in our uncertain present.

Spierdijk also wants the viewer to consider the girls psychologically, not just as unknown figures. The artist is known for predominantly painting girls, she is concerned with the female perspective and in this painting wants to give us a sense not just of the girl’s close relationship, but also of their unique differences, marking them as individuals. There is a protectiveness in the touch of the sister on the right of the piece, she sits higher with her arm around the shoulders and firmly on the forearm of the left sister. Perhaps she is older, her eyes seem to gaze slightly above the viewer as though she is thinking of their future. Whereas her sister’s gaze is direct, perhaps emboldened by the support she is receiving, or simply more focused on the present moment. However they are interpreted, there is undeniably a sense of quiet dignity to the figures, it is easy for the viewer to understand and perhaps even feel the emotional connection the sisters share.

Vincent Brown expresses a more complicated kind of familial bond in his ‘Hold Tight 2020’. The piece is incredibly personal, depicting his wife Liana and son Keanu, based on sketches and photographs he made more than a decade ago. The masks they wear give reference to the changes that Covid-19 has forced upon us. However, the artist originally made these as temporary additions that could be removed when the pandemic was over, creating an evolving work of art. Although the emotions expressed in the piece reflect current times, the original drawing was instead based on a brief period of homelessness Brown experienced with his wife and son. Through no fault of their own, they found themselves without a home and were placed in emergency accommodation with the help of the charity Shelter. Brown compares the helplessness and desperation they felt, to the Dorothea Lange’s photographs of people in Depression-era America. This inspired him towards the monochromatic/sepia toned colour palette. Although there are parallels to the ‘Sisters’ portrait, this protective bond between mother and child seems far more critical, with the child clinging to his mother for support and comfort.

There is something about the piece that is reminiscent of biblical depictions of the Virgin and child; light emanates from Liana’s head as she holds her innocent son. We are again faced with an image of a woman looking to the future with concern and the young person in her care gazing directly at the viewer. The boy’s eyes are piercing, almost determined, the viewer is forced to hold his stare and witness the maturity that has been forced upon him. His mother’s expression is far graver, as though she fears the potential permanence of their situation. Brown made two major alterations to the piece before submitting it to the exhibition, the first, was to cut it into a circular shape, inspired from when he had uploaded a photo of the piece to Facebook and the site had automatically edited it. The second was to cut into the drawing in order to make the masks, that originally had been applied with tracing paper and masking tape, a permanent aspect of the work. There is something very poignant about the idea of making something that was supposed to be temporary, effectively eternal.

Pieces that were created in lockdown conditions, unsurprisingly, share this tone of uncertainty and angst. Jacqueline Alkema’s ‘Flower Series - Oleander’ does this through the use of symbolism. ‘Oleander’ has a striking use of colour; it is completely monochromatic apart from a vein of diluted red running through the girl’s body, like roots, leading up to the flower on her right. The oleander flower is traditionally thought to symbolise desire and destiny, however Alkema included this poisonous flower as a means of creating an atmosphere of anxiety and isolation, reflecting the pandemic conditions in which the piece was created. ‘Flower Series- Oleander’ won second place in The Academy Prize. When asked about why it was chosen out of the 698 artworks included in this themeless exhibition, one of the judges explained that it was the quiet authority and power of the figure’s gaze. Her eyes are engaging with the viewer in an almost challenging way, it feels difficult to meet her stare. The artist entered this piece out of the series of 5, as she felt it was the most powerful, she had created an unknown woman and transformed her into something iconic. The girl appears as a figure of strength, facing this uncertain world, bold and unafraid.

As it progressed, I found that the pieces I was choosing to focus this tour on were largely representations of women. This was not by any means a conscious decision, but more likely related to the number of strong representations of female figures included. Depictions of free, powerful and resilient women still feel relatively new and refreshing in the history of art and seeing how modern artists tackle the subject is incredibly exciting.

Yolande Armstrong’s ‘Big Auntie Minnie and Friend’ also addresses ideas of strong female subjects. ‘Big Auntie Minnie’ is the left of the two figures depicted, she is the great aunt of Armstrong’s partner, Maggie. As such Armstrong was able to give a rare insight into the subject’s history. She describes Minnie as quite a powerful woman, especially for her time. She had no children, survived three husbands, ran her own business, bought her own house and travelled a lot in the fifties, all of which was somewhat unusual for the period. Armstrong sees her as a matriarchal figure, having a high degree of autonomy in her community. However, it was Minnie’s big personality and presence, not her history, that really drew the artist’s eye. The idea of a free spirit. Armstrong explained that she greatly admires Minnie’s sense of self-possession, even in old photos she claims to get a sense of a woman at ease with her body and self, able to simply enjoy the world. The painting is visually quite different from Armstrong’s other work, she explained that her process changed as she was trying to gain a sense of transience, focusing on the light and shade in the photograph she was working from. The figures are almost transparent, ghost like, unfixed in time, as though the original photograph had been bleached by the sun or aged by years. However, the firm presence of Minnie and her friend is still very clear, their gazes are assertive, confident and direct. Unlike many portraits of women from the past, there is nothing particularly flattering about this painting, it instead displays something unmistakeably real and honest.

Art has often been used not just to reflect a moment in history, but also to inspire those within it. It then begins to make sense to me why I was drawn to these particular pieces; Renee Spierdijk and Vincent Michael Brown’s pieces exhibit the strength that can be drawn from family during tough times, while Jaqueline Alkema and Yolande Armstrong have presented portraits that express female power and resilience. With everything that is currently occurring around us, these ideas can give us not just reassurance, but also a strong sense of hope.

To browse all of the 168 Annual Open artworks online click here